There lived in Hanyang a man called Chang Kien, whose young daughter, Chien, was of peerless beauty. He also had a nephew called Wang Chau–a very handsome boy. The children played together, and were fond of each other. Once Kien jestingly said to his nephew, “Someday I will marry you to my little daughter.” Both children remembered these words, and the believed themselves thus betrothed. When Chien grew up, a man of rank asked for her in marriage, and her father decided to agree. Chien was greatly troubled by this decision. As for Chau, he was so much angered and grieved that he resolved to leave home, and go to another province. The next day he got a boat ready for his journey, and after sunset, without bidding farewell to anyone, he proceeded up the river. But in the middle of the night he was startled by a voice calling to him, “Wait–it is me!”–and he saw a young woman running along the bank toward the boat. It was Chien. Chau was unspeakably delighted. She sprang into the boat, and the lovers found their way safely to the province of Chuh. In the province of Chuh they lived happily for six years, and they had two children. But Chien could not forget her parents, and often longed to see them again. At last, she said to Chau, “Because I could not bear to break the promise I made to you, I ran away with you and left my parents—although knowing that I owed them all possible duty and affection. Maybe we could go now and try to obtain their forgiveness” Chau agreed, and a few days later they returned to Hanyang. According to custom in such cases, Chau first went to the house of Kien, leaving Chien and the children in the boat. Kien welcomed his nephew with every sign of joy and said, “How much I have been longing to see you! I was often afraid that something had happened to you.” Chau answered respectfully, “I don’t deserve this kindness! We have come to beg your forgiveness!” But Kien did not seem to understand. He asked, “Forgiveness for what?” “I was sure,” said Chau, “that you would be angry with me for having run away with Chien, taking her with me to the province of Chuh.” “What Chien was that?” asked Kien. “Your daughter Chien,” answered Chau, beginning to suspect his father-in-law of some malevolent design. “What are you talking about?” cried Kien, completely astonished. “My daughter has been sick in bed all these years—ever since the time when you went away.” “Your daughter,” returned Chau, becoming angry, “has not been sick. She has been with me for six years, we married and had two children, and we have returned here only to seek your forgiveness. Please, do not mock us!” For a moment the two looked at each other in silence. Then Kien arose, and motioning to Chau to follow, led the way to an inner room where a sick woman was lying. And Chau, to his utter amazement, saw the face of Chien—beautiful, but strangely thin and pale. “She cannot speak,” said Kien, “but she can understand.” And Kien said to her, laughingly, “Chau tells me that you ran away with him, and that you have two children.” The sick woman looked at Chau and smiled, but remained silent. “Now come with me to the river,” said the bewildered Chau. “For I can assure you—in spite of what I have seen in this house—that your daughter Chien is in my boat at this very moment.” They went to the river, and there indeed was Chien, waiting. And seeing her father, she bowed down, begging his forgiveness. Kien said to her, “If you are truly my daughter, I have nothing but love for you. Yet, though you seem to be my daughter, there is something I cannot understand. Come with us to the house.” So the three proceeded toward the house. As they neared it, they saw that the sick woman—who had not left her bed for years—was coming to meet them, smiling as if much delighted, and the two Chiens walked toward each other, coming together in an embrace. But then, suddenly, they melted into each other and became one body, one person, one Chien, showing no sign of sickness or of sorrow. Kien said to Chau, “Ever since the day you left, my daughter could not speak, and most of the time was like person who had taken too much wine. Now I know that her spirit was absent.” Chien said, “Really, I never knew that I was at home. I saw Chau going away in silent anger, and that same night I dreamed that I ran after his boat. And now I cannot tell which was really me--the one that went away in the boat or the one who stayed home."

0 Comments

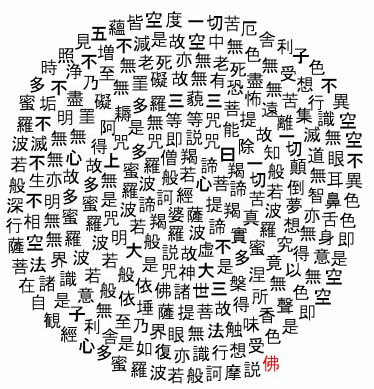

The news lately about Coronavirus has been dreadful and deeply upsetting. At times I've felt unwilling to accept all the change that this virus is bringing to our lives. From fear for our safety and well-being, to worries about work and school changes, to the cancellations of events left and right--"this shouldn't be happening!" I keep thinking. Today I found myself snapping at a colleague; it was only then that I realized how truly agitated I felt by the onslaught of news and concern for many beloveds. This evening I came home and had a good cry. I was able to really feel my fear, my protectiveness, and grief. This gave me a more grounded feeling, and I was able to meditate. And it hit me: We were made for this time! If you are a meditator, you've been cultivating the skills you need to get through the difficulties of this time. Qualities like acceptance, presence, adaptability, and radical compassion. This is the time we've been practicing for! And since it looks like we will be spending more time at home, its a perfect time to re-dedicate to practice. If you're interested in taking up this call to meditate, join our virtual sangha by Zoom this Sunday evening at 6:30. We'll do two rounds of meditation together, in the safety pf our own homes. And I'll give a dharma talk on Coronavirus and Meditation Practice at 7:30. Please join us!  A student asked her teacher, "What is Zen?" The teacher said, "The heart of the one who asks is Zen." When I first heard this koan, it seemed like good news! Perhaps my heart, too, is Zen, just as it is. In any condition, in grief or joy or longing, my own heart is acceptable; it doesn't have to be a problem to solve. And indeed, meditating in the seat of the heart is one of the most challenging, and most essential, of practices. In Zen, our way is to move into difficult emotions, instead of avoiding them. In this way, we find out more and more that our own heart is a wise teacher. But what is the heart the koan speaks of? Is it just the heart as the center of personal emotional feeling? While our emotions are an essential gate into practices of the heart, as we explore, we can find that our heart is so much bigger than that.  Beginning in March, we will be studying the Heart Sutra in our dharma study group. Here are three different translations of the Heart Sutra, each with a different flavor and inflection. Enjoy! The Heart Sutra Translated by Red Pine The noble Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, while practicing the deep practice of Prajnaparamita, looked upon the five skandhas and seeing they were empty of self-existence, said, “Here, Shariputra, form is emptiness, emptiness is form; emptiness is not separate from form, form is not separate from emptiness; whatever is form is emptiness, whatever is emptiness is form. The same holds for sensation and perception, memory and consciousness. Here, Shariputra, all dharmas are defined by emptiness not birth or destruction, purity or defilement, completeness or deficiency. Therefore, Shariputra, in emptiness there is no form, no sensation, no perception, no memory and no consciousness; no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body and no mind; no shape, no sound, no smell, no taste, no feeling and no thought; no element of perception, from eye to conceptual consciousness; no causal link, from ignorance to old age and death, and no end of causal link, from ignorance to old age and death; no suffering, no source, no relief, no path; no knowledge, no attainment and no non-attainment. Therefore, Shariputra, without attainment, bodhisattvas take refuge in Prajnaparamita and live without walls of the mind. Without walls of the mind and thus without fears, they see through delusions and finally nirvana. All buddhas past, present and future also take refuge in Prajnaparamita and realize unexcelled, perfect enlightenment. You should therefore know the great mantra of Prajnaparamita, the mantra of great magic, the unexcelled mantra, the mantra equal to the unequalled, which heals all suffering and is true, not false, the mantra in Prajnaparamita spoken thus: “Gate, gate, paragate, parasangate, bodhi svaha.” The Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore Translated by Thich Nhat Hanh Avalokiteshvara while practicing deeply with the Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore, suddenly discovered that all of the five Skandhas are equally empty, and with this realization he overcame all Ill-being. “Listen Sariputra, this Body itself is Emptiness and Emptiness itself is this Body. This Body is not other than Emptiness and Emptiness is not other than this Body. The same is true of Feelings, Perceptions, Mental Formations, and Consciousness. “Listen Sariputra, all phenomena bear the mark of Emptinesss; their true nature is the nature of no Birth no Death, no Being no Non-being, no Defilement no Immaculacy, no Increasing no Decreasing. “That is why in Emptiness, Body, Feelings, Perceptions, Mental Formations and Consciousness are not separate self entities. “The Eighteen Realms of Phenomena which are the six Sense Organs, the six Sense Objects, and the six Consciousnesses are also not separate self entities. “The Twelve Links of Interdependent Arising and their Extinction are also not separate self entities. “Ill-being, the Causes of Ill-being, the End of Ill-being, the Path, insight and attainment, are also not separate self entities. “Whoever can see this no longer needs anything to attain. “Bodhisattvas who practice the Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore see no more obstacles in their mind, and because there are no more obstacles in their mind, they can overcome all fear, destroy all wrong perceptions and realize Perfect Nirvana. “All Buddhas in the past, present, and future by practicing the Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore are all capable of attaining Authentic and Perfect Enlightenment. “Therefore Sariputra, it should be known that the Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore is a Great Mantra, the most illuminating mantra, the highest mantra, a mantra beyond compare, the True Wisdom that has the power to put an end to all kinds of suffering. Therefore let us proclaim a mantra to praise the Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore. “Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha! Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha! Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha!” The Great Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, practicing deep Prajna Paramita clearly saw that all five skandhas are empty, transforming all suffering and distress. Shariputra, form is no other than emptiness, emptiness no other than form; form is exactly emptiness, emptiness exactly form; sensation, perception, mental reaction, consciousness are also like this. Shariputra, all things are essentially empty-- not born, not destroyed; not stained, not pure; without loss, without gain. Therefore in emptiness there is no form, no sensation, perception, mental reaction, consciousness; no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind; no color, sound, smell, taste, touch, object of thought; no seeing and so on to no thinking; no ignorance and also no ending of ignorance, and so on to no old age and death and also no ending of old age and death; no suffering, cause of suffering, cessation, path, no wisdom and no attainment. ❍ Since there is nothing to attain, the bodhisattva lives by Prajna Paramita, The Open Source 1-2 Cantor Manual with no hindrance in the mind; no hindrance, and therefore no fear; far beyond delusive thinking, right here is Nirvana. ❍ All Buddhas of past, present and future live by Prajna Paramita, attaining Anuttara-samyak-sambodhi. Therefore know that Prajna Paramita is the great sacred mantra, the great vivid mantra, the unsurpassed mantra, the supreme mantra, which completely removes all suffering. This is truth, not mere formality. Therefore set forth the Prajna Paramita mantra. Set forth this mantra and proclaim: Sung—3 times ( during ceremony, until everyone has made offering at altar): ❍ Gaté Gaté Paragaté ❍ Parasamgaté ❍ Bodhi Svaha!  Luckily, being heartbroken is a perfect opportunity to practice the dharma. Good news for those of us with achy breaky hearts. But why? Because you have already had the rug pulled out from under you. You have already experienced a great loss. You know what it is to walk in groundlessness, with so much stripped away. In this state, you are open to something new. How about the Heart Sutra, the great Buddhist teaching on compassion? The Heart Sutra doesn't seem like an antidote to a broken heart at first. There are no, ahem, warm fuzzies here. No consolation, no reassurance, no nothing! In fact, the primary word in the Heart Sutra is the word "No"! Many Zen student's say they don't like the Heart Sutra. "It's too negative." The Heart Sutra is a concise and shocking teaching directly from Avalokiteshvara, the gender fluid bodhisattva compassion. This courageous warrior, also known as Quan yin and Kanzeon, expresses their experience of the highest teaching of the Buddha in this sutra. Their insight was not based on intellect but came through their practice and life experience. Then one of the principal disciples of the Buddha, a monk named Shariputra, began to question Avalokiteshvara. This is an important point. Even though a great bodhisattva was teaching, the profound meaning emerged only through questioning. Nothing is taken on blind faith. Avalokiteshvara answered with the most famous of Buddhist paradoxes: “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form. Form is no other than emptiness, emptiness no other than form.” When I first heard this, I had no idea what it was talking about. It just made no sense, and my mind drew a blank. The sutra, like life itself, is inexpressible, indescribable, inconceivable. What is this emptiness, anyway? It's not vacancy, or nihilistic nothingness. Rather, it points toward the fact that nothing has a permanent form, but rather is in a process of becoming and falling away. So the "emptiness" in Buddhism is our lack of permanent and separate existence. We are interdependent, and we are becoming, anything is possible. When we perceive the experiences of our lives as empty, without any barriers or veils, we understand the perfection of things just as they are. So when Avalokiteshvara says, “Form is emptiness,” they're referring to this simple direct relationship with the immediacy of experience—direct contact with heartbreak; with love and hate. We go beyond our story of right and wrong, of blame or grievance. We keep pulling out our own rug. When we perceive form as empty, without any barriers or veils, we understand the perfection of things just as they are. One could become addicted to this experience. It could give us a sense of freedom from the dubiousness of our emotions and the illusion that we could dangle above the messiness of our lives. But “emptiness is form” turns the tables. Emptiness continually manifests as war and peace, as heartbreak, as birth, old age, sickness, and death, as well as joy. We are challenged to stay in touch with the heart-throbbing quality of being alive. That's where practice comes in, meditation and study. If you'd like to join a small group studying the Heart Sutra, join us here!  I'm just back from the annual meeting of the Lay Zen Teacher's Association in Joshua Tree, CA. What a wonderful, warm-hearted and deep-spirited group of humans! The meeting was truly special, and I learned more than I can possibly capture here. Much of that learning happened casually, in conversations over meals, in watching the practices of others, and seeing the ways we are different (and similar). I came away deeply encouraged about the future of the dharma and the many ways it is illuminated. The meeting kicked off with a presentation by Ryodo Hawley of ZCLA on "The Threes of Zen." He talked about a workshop he has offered to give people an overview of what happens in Zen practice, how our attention can move from our habits and opinions, to a more observational stance, through simple presence, then on to inquiry and bodhisattva action. His model is elegant, and we found ourselves referring to it often as the conference went on. Next I offered a training in "Meditation and Trauma." I taught the group about how trauma impacts the brain, and how that can show up in meditation practice. I sought to help each participant become a trauma-informed Zen teacher, able to work with people whose trauma may be activated with kindness and skill. The feedback on the workshop was really positive, and many people reflected on the sometimes subtle ways trauma can show up in spiritual work--including for teachers. The next two days included many wonderful panels and break-out groups. I learned about sangha leadership, the council process of group communication, working with aging and dementia in the sangha, Zen and social justice, and talking about whiteness. I offered a session called "Koan Innovation," in which we talked about creative ways to bring koan work to groups. We also had some ceremony, and people from different sanghas took turns leading morning meditation and service. Oh, and we had some fun! (Zen charades, anyone?) The lunar eclipse was marvelous and clear in the dark desert sky. Some of us went to a local hangout for dinner and a beer, and we also went hiking in Joshua Tree National Park (yes, it was open and free, no trash to be found!) What stands out the most is the utter kindness and lack of pretense of the people there. LZTA has become like a family to me, and I plan to return as often as I can. Words from my teacher Joan Sutherland Roshi on our election this week.

If you can vote, you have the immeasurable honor of casting yr ballot for those who can't - for Black and Jewish Americans gunned down while they worship ... for students gunned down at school ... for every Native American and African American and Latinx person whose vote was stolen from them ... for children ... for refugees met at the border by the military ... for people you will never meet, living in countries affected by our policies ... for the generations of our foremothers who couldn't vote ... for the climate and the waters, the animals and insects struggling against extinction - as if we're one tribe as if we're one tribe. Vote what you love and what has loved you ... Vote what you believe in, vote what you don't believe in anymore so it can find its way back to you ... Vote the sunrise and the sky-filled stars, cousins with feathers and aunties who graze, grasses that bend in the wind and grasses that push up through the pavement ... Vote yr broken, fierce heart ... Vote for the day after tomorrow, which will come which will come. Make yr vote as wide as the sky, as steady as the earth ... Make yr vote a prayer.  An old story: The enlighted lay practitioner Vimalakirti became sick. A group of bodhisattvas were curious about how such an enlightened person could fall ill, so they went to ask him about it. They asked him, "Why are you sick?" Vimalakirti said, "I am sick because the whole world is sick. If everyone's illness were healed, mine would be too. Why? Because bodhisattvas come into this world of birth and death for the sake of all beings, and part of being in this world of birth and death is getting sick. When everyone is liberated from illness, I will be, too." Like Vimalakirti, I haven't been feeling too good lately. I'm feeling tired, exhausted really, and pretty beaten up. I am prone to fits of rage and despair. My body is in it too, dysregulated in distressing ways. Our latest social trauma, the Kavanaugh debacle, has so many of us contending with both personal and political re-traumatization that can feel soul-crushing. It's literally sickening. It's a sickness with many names: patriarchy, ;ate-stage capitalism, plain old greed, take your pick. I'll let the other brilliant writers take on the nature of this illness, and it's prognosis. In the mean time, we have to find a way to live in the midst of this shit show. What's a bodhisattva to do? Vimalakirti points the way. We are each sick because our world is sick. In other words, we are interdependent with each other. The world and I have one condition; I am the sorrows of the world. When the world is healed, I am healed, and we can each have a role in that. It's a poignant thing, to be very sick together, and still able to find ways to offer healing. Bodhisattvas are born in the moment any of us takes a deep breath, rolls up our sleeves, and does the next right and courageous thing. In Buddhism we take up the Bodhisattva Way to help us become more and more discerning of this path. It involves taking vows that help show us the way, as well as practices that allow us to live into this Way. It's pretty helpful at times like these. And it's pretty helpful to do it together.  I'm getting ready to present on a panel on "mindfulness" tomorrow at the APA conference now happening in San Francisco. (If you happen to be there 8-10 am tomorrow swing on by!) By the way, have you ever meditated like this? Me neither! Other presenters will be talking about the clinical applications of mindfulness in our work as psychologists. I was asked to talk about "mindfulness" from the point of view of the Zen tradition. I have lots of thoughts, and will share a few. First, I think it a really good thing that many people are benefiting from learning mindfulness meditation. It has become an outpost of presence and sanity in our otherwise insane world. However, it is crucial to be aware that mindfulness is not the same as meditation, and certainly not Buddhist meditation. The contemporary practice of mindfulness has a number of radical differences from the practice of Zen. First of all, Zen practice includes meditation in the context of a system of ethics, and in the presence of an old spiritual and religious practice. Mindfulness, along with concentration and inquiry, are the traditional foundations of meditation practice in Zen. These practices are taken up in a community, with a teacher, and in the context of study of spiritual teachings. Practitioners go through training on the Buddhist ethical system, the precepts and the paramitas, in conjunction with meditation practice. Zen practice is not taken up for personal self-improvement, though that may be a welcome side effect. Rather it is taken up so we may wake up to the radical truth of interdependence. When we truly witness and live into our place in the family of things, the only thing to do is to take up the bodhisattva way, at the heart of our tradition. We vow to be a part of the awakening of all beings (including but not limited to ourselves), as best as we are able. Mindfulness as a psychological technique is torn out of the cultural, spiritual, and religious context of Buddhism. And, along the way, it inverts the spirit of practice, toward a commodity that can be used for personal healing or self-improvement. It becomes a goal in itself, something to do well or poorly, an offering at the buffet of self-improvement goods. It is something that is measured, calculated for benefit, optimized, and commodified. It is offered in expensive retreats, corporate training, and as a remedy for depression, stress, and other ailments. My other concern about the mindfulness movement is that it privileges the conscious mind and our control of it. It's no wonder mindfulness has been so utilized in cognitive-behavioral approaches. Mindfulness as often taught emphasized becoming more aware of the conscious mind and what happens in it. All good stuff! However in Zen we also take up the aspects of the mind that are not in our awareness, the unknown, embryonic states, weird and tilty places, intimations of the vastness. In this way I see Zen practice as a great complement to psychoanalytic psychotherapy! As a Zen teacher, I worry that Westerners will come to think that mindfulness is what meditation practice is. While mindfulness practices can be really helpful, they are just one strand of a deep and rich tradition, with many other practices, teachings, and ancestral wisdom. Given the dominance of the mindfulness and vipassana practices these days, what does it mean to practice Zen? How is it different? And how does it impact one differently as a therapist or practitioner? If you have thoughts, please comment!  Suddenly I realized for myself the fresh breeze that rises up when the great burden is laid down. -Fayan Most of us go through life with a feeling of struggle. We may have the feeling that there is something wrong with us that we must fix. Or perhaps it's a constant sense that the world is not the way we want it to be, leading to chronic resentment and distress. And, of course, there's our partner, our parents, or kids, or boss, who definitely need to change in order for things to be alright. And, when we begin to meditate, we find struggle there too. Our mind wanders constantly, and we have the sense of not being able to do it right. We imagine that when we meditate we should be calm, present, and compassionate, but so often that's not at all what's happening. It's easy to give up. At the core of our struggle is not wanting to be with life as it is. We feel a constant need to figure out the problem and fix it, with ourselves, with our relationships, with society, and even in our meditation. In fact, we become addicted to struggle. We have formed our identity around it, around our narrative that "The problem is.... (fill in the blank)." We put tons of mental and emotional energy into trying to fix things so that they are the way we think they need to be, and then casting blame when this doesn't work. Constant discontent. Constant struggle. How can we, like Fayan, put down the great burden and experience the fresh breeze of intimacy with the world as it is? We can begin to explore this in our meditation. The key is acceptance of what is, without judgment. Your mind, just as it is, even in it's jumpiness or confusion or anxiety, doesn't need to change. We can welcome our experience with kindness and curiosity, just as it is. Put down the great burden of struggle, of judgment and comparison, of right and wrong, good and bad. Beyond our attempts to "fix" and control life, there is a way to walk in the fresh breeze of life as it is. I'll meet you there. |

Details

AuthorMegan Rundel is the resident teacher at the Crimson Gate Meditation Community in Oakland, CA.. Archives

April 2020

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed