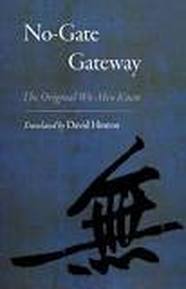

I've been keeping company for the past few weeks with No-Gate Gateway, David Hinton's luminous new translation of the Mumonkan. This collection of koans (or sangha cases, as Hinton calls them) has been widely used for centuries, but until now most of our English translations have been done from the Japanese. Hinton is a translator and scholar of classical Chinese, and at the heart of this text is his fresh explication of the history and meaning of the original characters in the koans. Hinton emphasizes Zen's roots in Taoist philosophy, especially the dialectic between what he calls Absence (emptiness, formlessness) and Presence (form, existence). I believe No-Gate Gateway will help make koan practice vital and approachable for the next generation of Zen students. I found No-Gate Gateway to be a fresh and exciting approach to these koans. Over and over, koans that are old friends gained new energy and layers of meaning. The introduction alone is essential reading for any student of Zen. Here he puts forth his "wilderness cosmology" of a universe in perpetual transformation. Hinton describes the character for Absence as originating in a pictograph of a woman dancing with foxtails streaming from her hands, an expressive and evocative depiction that belies any sense of nihilism. The character for Absence can also be used for a simple "no" (as in mu and wu), and this doubling of meaning threads throughout the text. He says that in meditation, "eventually the stream of thought falls silent, and we inhabit empty consciousness, free of that center of identity. That is, we inhabit the most fundamental nature of consciousness, an that fundamental nature is nothing other than Absence." Hinton translates the first koan in the collection, often know as Chao-cho's Mu, as follows: A monk asked Master Visitation-Land: "A dog too has Buddha-nature, no?" "Absence," Land replied. No-Gate Gateway offers a fresh, intimate, and clear take on koan practice, and, I believe, will help the Mumonkan to continue to dance for the next generation of Western Zen students. Because it is anchored in the rhythms of nature, it helps us respond in times of ecological crisis. Because it is wildly poetic, it captures the sweep of the koans, from the inexpressably vast to the deeply personal. And because it is rooted in an understanding of ancient China, it helps us anchor our practice in our own times. There are aspects of this book that I am grappling with. Hinton's new terminology can feel overworked and reliant on his explication. For example, a term he uses as synonymous with Absence is origin-tissue, defined as "reality as a single tissue, undifferentiated and generative." While I appreciate the poetry here, it's hard to imagine this as a usable term. Similarly, he translates the names of people and places in a way that is hard to get used to. Chao-cho is now Visitation-Land, another shift that is provocative and hard to adapt to.

0 Comments

Western models of the unconscious mind have shifted in exciting ways over the past one hundred years. From Freud's repressed and dynamic models of the unconscious, we have expanded to think about relational, cultural, and ecological dimensions to the aspects of mind of which we are not consciously aware. An emphasis on making the unconscious (more) conscious is at the heart of contemporary depth models of psychotherapy.

Meditation is also a way of coming into relationship with our unconscious mind in a different way. Anyone who has done a meditation retreat knows that aspects of the hidden mind swarm around, and it's not easy to distract ourselves. The first five or so years of my own practice was a messy karmic purge of old fear, rage, and desolation. As usual the practice was just to sit with it, not avoiding or fixing or dramatizing. And, in meditation, there are moments when all the stories drop away, when our personal psychology gives way to the vastness. We have experiences of deep stillness and absolute interconnection. What we consider to be the "self" is radically altered. Though, for better and for worse, our personalities remain! Buddhism has a fascinating model of the "storehouse consciousness" in which all the seeds of our karma, and those of generations preceding us, incubate and give rise to our current karma. One fruit of meditation, according to this teaching, is to understand and uproot this karma. But, that's a topic for another day--one I hope to teach soon. In a life of practice, we become intimate with many aspect of the unconscious. Here are a few I notice. I'm curious about your experience! -The everyday level of shifting moods, habits, and relational patterns, our "autopilot." -The deep personal unconscious, the stuff that repeats and reminds us of our childhood and which we'd do anything to escape but we can't... (And which we secretly hope meditation will fix but really we just marinate in it.) -The aspect of the unconscious that is bigger than the self. From the relational dynamics between two people to currents present in generations of families, cultures, and groups of all kinds. At this level we know we are part of something bigger than ourselves. -The level of the Absolute. This is impossible to talk about, but we try with language like God or emptiness. Here we find that any personal or transpersonal unconscious is co-extensive with everything, creating a vast and beautiful flow. Each of these levels of Mind are present at all times, but mostly we are unaware of them. How they relate to each other, and how we can skillfully work with them, is a fascinating work in progress. I look forward to talking together about this! |

Details

AuthorMegan Rundel is the resident teacher at the Crimson Gate Meditation Community in Oakland, CA.. Archives

April 2020

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed