So what do we actually do when we are meditating? In our tradition, the core practice is called zazen. This is seated meditation practice that helps us settle the mind, experience whatever is happening intimately, and cultivate insight into the true nature of life. For beginning instructions on zazen, you can go here. We begin by counting our breaths, and may move on to shikantaza, or just sitting. Zazen is the practice of a lifetime, and the cornerstone to which we can return no matter the condition of our experience. Many people find that they develop a palette of meditation practices, to work with particular circumstances and difficulties or to develop spiritual insight. It's part of our skillful means in practice to discern what meditation practice is most suited to a particular time in life (a teacher comes in handy here). While there are many such practices, I'll describe some that I have found most helpful here. In times of great emotional difficulty, either our own or our experience of suffering with the world, the practice of tonglen. Tonglen doesn't get rid of our suffering, but rather helps us relate to it with less fear and aversion. The fundamental practice is that we breathe in what is difficult and painful; we breathe in the suffering . We breathe out spaciousness, ease, happiness—the things that help dispel suffering. In acting to dispel the sufferings of others, we also dispel our fear of our own suffering. For more instruction on tonglen practice, go here. If you are feeling self-critical, depressed, or exhausted, lovingkindness (metta) practice might be just the right thing. In this practice, we direct love, safety, peace, and ease toward ourselves and others. Lovingkindness practice actively cultivates a generous, gentle presence and is a great practice for all of us who could use more of these qualities. In this practice we learn that we have to be able to direct loving care and acceptance toward ourselves before we will truly be able to offer these to others. For more instruction on metta, go here. If you are somewhat stable in your meditation practice, you might consider taking up koan practice, either formally or informally. Koans help catalyze the spiritual imagination, and systematically cultivate insight into our true nature. Koans invite us to bring our whole selves into meditation practice, and offer a way of shaking up our usual way of seeing things. Koan practice is intrinsically relational, and formal koan study is done in intimate and ongoing relationship with a teacher. Form more information on koan practice, go here. There are other practices that we take up in Zen. Walking meditation, chanting sutras, sangha service, and taking the precepts are traditional and profound arenas of practice. One of the benefits of becoming committed to a sangha and a practice over time is the opportunity to immerse ourselves in these teachings. Many Zen students find that it is natural to extend the experience of zazen into a movement practice (yoga, tai chi, running, dancing, etc.), creative art practice (music, visual art, writing, etc.), or a professional or service practice (psychotherapy, community service, etc.). Indeed as our Zen practice develops we find it informs all of our activities. And, in every moment, we can always find our way back to our breath. In my next post, I'll take up the intriguing topic of the benefits of meditation. Is it worth it, and what changes for people to take up this Way?

0 Comments

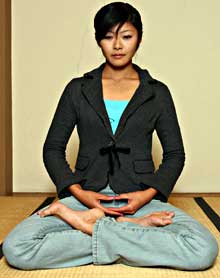

To really grow in our spiritual life, it is important for most people to establish a regular practice of meditation. But what does this actually look like, and what are its benefits? In this post and the next few to follow, I'll break it down, from a Zen point of view. In the Zen tradition, there are four pillars of practice. The first is what I call daily-ish home practice. What this means is, you find someplace in your home where you can keep a pillow or chair on which to meditate. It's good if it's a place free from too much intrusion or distraction. Maybe you can even have a little altar with figures that are important to you, and a candle. Then, you sit there every day. Regularity is more important than duration of time. If you can meditate almost every day for five or ten minutes, that's a great start. As you start to notice the impact of this practice on your life, you may find you naturally want to extend it. The second pillar of Zen practice is sangha, or community. When we sit with a group of like-minded people, we express our commitment to supporting our own and each others' practices. Many people find that practice in a group is much different from sitting alone, and offers tremendous amount of power and growth. Sangha can also mean working with a teacher to support and deepen our practice. When we meditate with others, we find out what it means to make relationships and community a core focus of our practice, instead of feeling spiritual life to be set apart from the relational world. The third pillar of practice is everyday life. At first, meditation can seem like some special state that is different from what's happening when we are doing the dishes or tending to a sick child or writing a letter to our Senator. But as our commitment to the Way grows, we find that it is everywhere, and that every moment of life is an opportunity to practice. We are always fine-tuning and expanding that, and koan practice is a way to bring the practice of inquiry into everyday living. The fourth pillar of practice is retreat practice, ranging from half-day to week-long and even longer periods of intensive meditation practice. In Zen we call these retreats sesshin, which translates to touch the heart-mind. In retreat, we have a chance to let everyday cares fall away, to settle deeply into practice, to be in community with others, and to work closely with a teacher who can support and sometimes challenge our understanding. Many practitioners find that doing a retreat or two per year is immensely rewarding. In my next post, I'll describe what we actually do in our meditation practice, and how to develop a palette of practices to be used skillfully at points of different needs. |

Details

AuthorMegan Rundel is the resident teacher at the Crimson Gate Meditation Community in Oakland, CA.. Archives

April 2020

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed